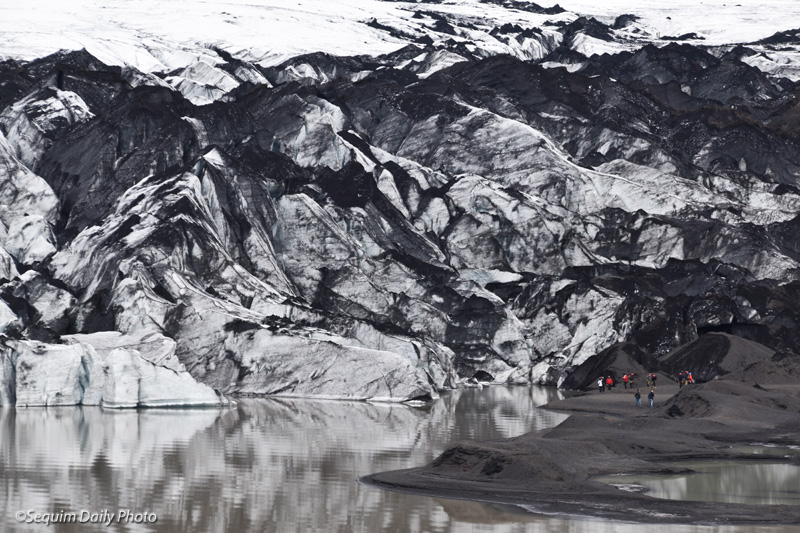

On one of two bus tours we visited Solheimajokull, part of the Myrdalsjokull Glacier. Iceland is a land of glaciers and this is the fourth largest, though like others around the world, this one is melting and retreating. To get an idea of the size of this glacial tongue, note the small, colored dots on the right of the shot above. Those are people.

Several years ago, the land on the left side of this photo was covered by the glacier. As you can see, it’s now exposed and a small lake has formed at its base.

Huge blocks of ice have calved from the glacier and float in the lake below. The black that you see on the ice and glacier are ash from volcanic eruptions including one volcano, Katla, that is hidden beneath the glacier.

Katla, unlike erupting peaks that may be more familiar to us, erupts from under the glacier, causing enormous glacial outbursts as the ice melts into massive floodwaters that can cover surrounding lands and flow for days. It is also accompanied by dense ash like you see in these photos as well as toxic fumes. Since Iceland was settled (sometime after 700 A.D.) Katla has on average erupted twice a century. The last eruption was in 1918.

Melting glaciers present a unique danger in Iceland. The weight of the ice may serve to cap volcanic activity beneath them. Will the volcanoes become more active as the weight above them is reduced?